12 May 2016

Imre Ámos, Painter of the Apocalypse

The exhibition of Imre Ámos, Painter of the Apocalypse opened at the Gallery of the Hungarian Academy in Rome on 11 February 2016, under the anspices of the Balassi Institute of Budapest. The occasion inaugurated Hungary’s assumption of the rotating annual presidency of the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance (IHRA). Culled by Katalin Petényi from the collections held by the Hungarian National Gallery and the Ferenczy Museum in Szentendre, the exhibition presented Ámos’s oeuvre through 52 works including early lyrical paintings, forcefully symbolic oil canvases, ink drawings, the harrowing Apocalypse series and, representing the epitaph of the painter’s work, some of the most important pieces in the Szolnok Sketchbook. The curators were Katalin Petényi and Pál Németh. The purport of the exhibition is underlined by the fact that this was the first time the painter’s work had ever been shown outside Hungary.

The vernissage was attended by several members of the Rome Jewish Community, including Giacomo Moscati, vice president for cultural affairs and Ruth Dureghello, the Community’s President, as well as Israel’s Ambassador to the Holy See, Zion Evrony. Eduard Habsburg, Hungary’s Ambassador to the Holy See, invited fellow Ambassadors from the United Kingdom, Belgium, the Netherlands, Japan, Romania and Bosnia-Herzegovina for a visit to the exhibition hosted by the Academy. Indicating the resounding success of the exhibition, talks are now underway for showing the painter’s work in Israel.

Also under the auspices of Hungary’s presidency of the IHRA and hosted by the Academy, a screening of short films about the heritage of the Hungarian Jewry was held between 4 and 11 February 2016. The festival commenced at 19:00 o’clock on 4 February with the screening of In the Land of Wonder Rabbis (1984, 60 mins.), a documentary by Imre Gyöngyössy, Katalin Petényi and Barna Kabay that was banned for six years and had not been shown in Hungary until after the democratic turn. It was followed the same evening by The Revolt of Job (1983, 105 mins.), a feature film directed by Imre Gyöngyössy and Barna Kabay, which had earned a nomination for the Academy Awards in its day. The festival ended on a poignant note a week later, on 11 February, with the screening of Ámos, Painter of the Apocalypse, a documentary by art historian-director Katalin Petényi and director-producer Barna Kabay. All films were shown with original Hungarian sound and Italian subtitles. The highly successful series of events was attended by Ms Petényi and Mr Kabay in person.

Antal Molnár

***

Inter arma silent musae – “In times of war, the muses fall silent” – goes the Latin proverb coined two thousand years ago. It is a saying that happens to be refuted by the oeuvre of the painter Imre Ámos. Bound to tradition, constantly musing on things past and given to introspection, Ámos left us a body of work that came into its own precisely during World War II. Until then, Ámos had willingly succumbed to the allure of myths and dreams, but when the war broke out he was driven by the cataclysm of history to recognise his own moral responsibility. As humanity came under increasingly fierce assault by Nazism, his faith and powers of prophecy both swelled despite his lyricist make-up. There was no turning back: Ámos now had to acknowledge and engage with his age and his contemporaries.

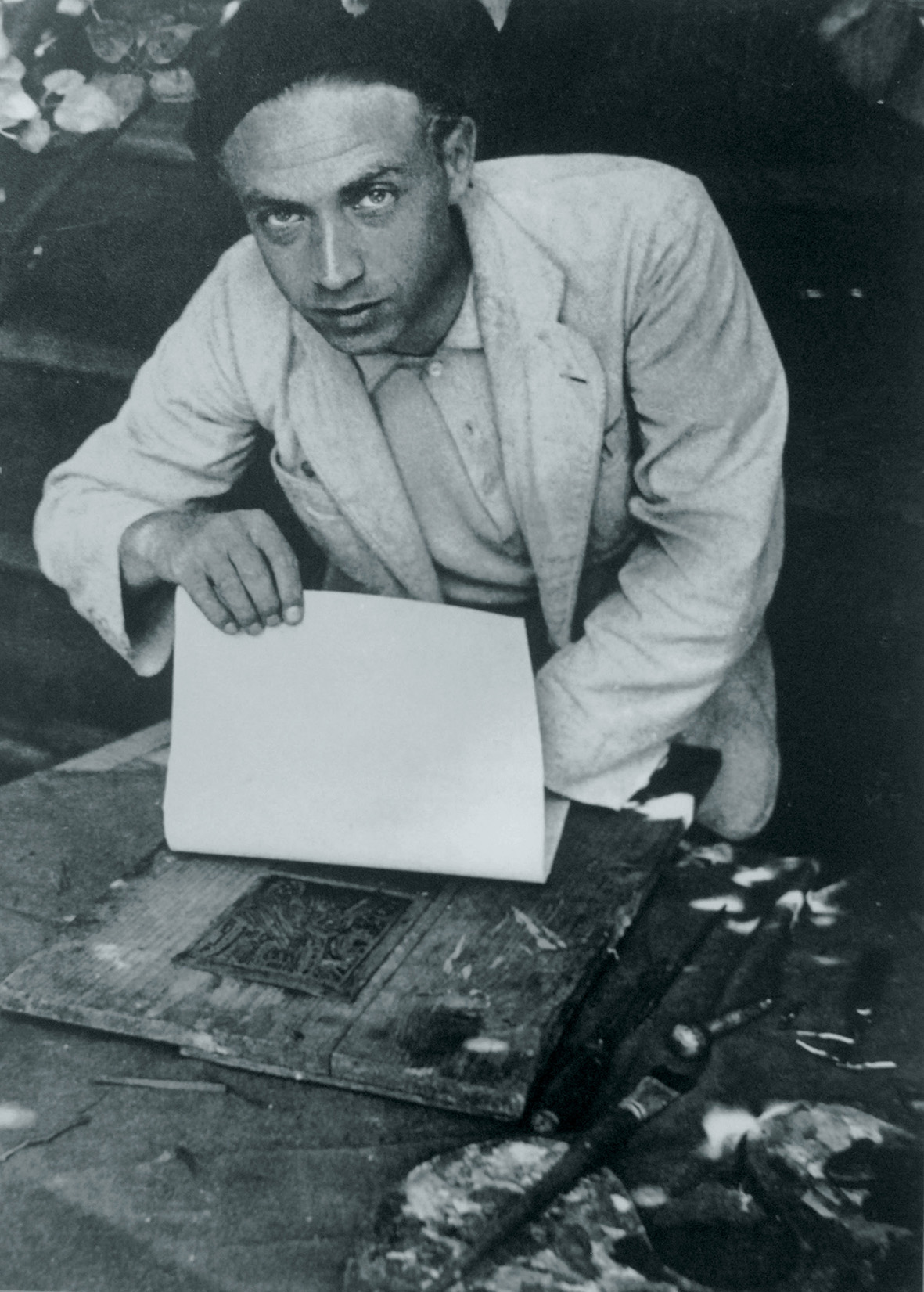

Imre Ámos working on his linocut series From Water to Water, 1934

Like his Biblical forebears, Ámos had a mission in life. And like Isaiah, he had his lips scorched by the burning coal of God. With the remote tranquillity of Arcadia receding from him to remain forever out of reach, the painter was swept up inexorably by the tempest of the times and was dropped, without a chance to grasp at the last straw of ordinary beauty, in the midst of the turmoil of reality. At this point he took up arms against historic violence by abandoning aestheticism and the formal problems of imagery, in order to turn toward the fundamental ethical questions of human existence forced upon him by the age. His style, too, underwent profound transformation. He began to use universal symbols of balladic conciseness to paint a vision of Europe’s danse macabre.

Ámos is now possessed of an ethos that shines through all his works and writings even in the direst adversity. Europe, of course, pays no heed to the “signs from heaven” as it rushes headlong toward its ruinous destiny. Ámos fights forlorn at the fronts and the lagers. He keeps working and creating to the last minute of his life. His fragile and delicate drawings stand as a disturbing memento to the horrors of forced labour. Identifying with the helpless and armed with prophetic faith and fortitude, he bequeaths his work upon us as a testimony to the chosen ones in their abhorrence of violence and confidence of the power of truth.

Imre Ámos – named Ungár by birth – first saw the light of day on 7 December 1907 in Nagykálló (or simply Kálló), one of the most ancient settlements in northeastern Hungary’s remote Szabolcs county. His father, Zsigmond Ungár was a retailer in a long line of grocers, haberdashers and market vendors in the family. His mother, Paula Liszer, widowed early and moved back to her parents’ house. His grandfather, Adolf Liszer, a cantor, Talmud scholar and a respected local schoolteacher, was an erudite, enlightened man who valued learning over material possessions, yet he did not raise his children and grandchildren in the strict Orthodox tradition. Instead, he would tell his grandson wonderful stories about the Kabbalah, the teachings of the Torah, the legends of Rabbi Isaac (Eizek) Taub, as well as Biblical stories about Christ. It was in his grandfather’s house that Ámos was first exposed to myth and the lore of the land where wonder rabbis were born, and these would remain a decisive influence to the end of his life.

In the interwar years, the small town of Kálló (Kaliv or Kalov in Yiddish), along with other settlements along the Tisza and Bodrog rivers, was the home of a unique and burgeoning rural Hasidic culture founded by Baal Shem Tov, whose teachings had given ordinary, poor people hope after the pogroms from which they fled to Hungary. The new branch of Judaism had arrived in the Carpathian Basin from Galicia in the 18th century, and soon attained widespread popularity.

In addition to strict abidance by the laws, Hasidism advocated devotion, goodwill and purity of the soul, and direct communion between man and God. Shepherds and farmers came round to believing that God lived in all things and creatures terrestrial, and that therefore each man was responsible for his thoughts and actions. The true purpose of man was to please others and find spiritual harmony. They believed that good would always triumph over evil, just as it invariably happened in legends. They discovered the beauty of life. They praised God not just by prayer but by work, song and dance – all of which went by the name of “service in joy”.

As a child, Ámos heard many a story about Rabbi Eizik Taub of Nagykálló, a shepherd boy turned venerable tzadik (wonder rabbi) and soothsayer whose legend had spread by word of mouth from generation to generation. Herdsmen, ploughmen and wagonners believed that the tzadik could work miracles even in his death. Pilgrims from faraway lands would write their wishes on a slip of paper and cast it to his grave.

In Hasidic legend, as in the paintings of Ámos, fragments of reality blend with longed-for miracles in a world in which life is complemented by dreams in the most natural manner. Indeed, his paintings frequently invoke the figure of a tzadik lost in reverie.

The painter’s sheltered childhood in Kálló equipped him with faith both religious and human, as well as a strong moral foundation and a sense of being protected.

He passed his matriculation exams with flying colours in 1925 at the local State Grammar School. Soon afterwards he moved to Budapest where he got a job as a silversmith and painter at the Lang Machine Factory. At the behest of his family, in 1927 he enrolled at the University of Technology where he completed two years in general engineering. In 1929, a childhood dream came true when he gained admission to the Budapest Academy of Fine Arts. His master, Gyula Rudnay, was quick to discover the young Ámos’s formidable talent.

He had signed his enrolment forms Ungár, his original family name, which he changed to Ámos in 1929. His early paintings are autographed by the interlocking initials “UAI”. Ámos – the name of the first minor prophet of the Bible – was a very apt and deliberate choice on the part of a fledgling artist who had heard and answered a prophetic calling.

The oil on canvas works Self-Portrait with Ady’s Mask and Winter, painted as an art student in 1930, carry on with the post-impressionist legacy. Both paintings prominently feature the death mask of the poet Endre Ady, leaving no doubt about the artist’s intellectual affiliation.

In 1931, at the private art school of Béla Kreisl, he made the acquaintance of Margit Anna, then 17 years of age, who studied painting under János Vaszary. In her he found a lifelong friend and true companion. The various facets of this complex relationship, the inextricable entanglement of two lives, are documented in their diary entries and correspondence.

During the summer he would return to his home town and paint portraits of his family and himself, invariably presenting his subjects in their natural environment, in the company of a cherished object belonging to them. The formal solutions of the early paintings show the influence of the Nabis, Bonnard, József Rippl-Rónai and Róbert Berény, but while these great precursors rely heavily on decorative and sensual effect, Ámos is more interested in spiritual contemplation. His general outlook, as he explains in his diary, links him more intimately to Chagall, Csontváry and Gulácsy, particularly in terms of picturesque vision, a penchant for dreams and the liberating imagination, and a susceptibility for the esoteric.

Women at the Spring, 1935

In August 1934, he made a 30-sheet series of linocuts portraying the loneliness of destitute people turned homeless in the big city. The epic narrative thrust of From Water to Water is underlain by a subplot of personal experience of a young painter uprooted from the local community of Kálló. The series sets up a stark contrast between the modern urban environment and the loneliness of man conceived in nature and innocence, depicting the conflict with the characteristic, powerful terseness of a ballad.

Ámos graduated from the Academy of Fine Arts in 1934. Even before that, since 1931, he had been regularly showing work at the Spring Exhibition of Young Artists hosted by the National Salon of the Szinyei Society, which awarded him its eponymous prize in 1934. The Municipal Gallery of Budapest purchased one of his paintings. The following year he had no fewer than 37 paintings on display at the Group Exhibition No. CLII curated by the Ernst Museum.

Before my Great-Grandmother’s Mirror, 1935

One of the outstanding works shown at the Ernst was his Women at the Spring, from 1935. “[In the pool] lay a great multitude […] waiting for the moving of the water. For an angel went down at a certain season into the pool, and troubled the water: whosoever then first after the troubling of the water stepped in was made whole of whatsoever disease he had” (John 5: 3-4, King James Version). In Ámos’s painting, however, it is not the lame and the blind but young girls and old women suffering from the solitude of the soul who are waiting for the miracle, for the cure of wounds invisible to the eye, for spiritual rebirth. With eyes half closed and lost in reverie, they only see the distance. The faces exude mystery and sorrow; the eyes grief over man’s transience. Behind them is the spring of water that is the eternal symbol of life, as they wait patiently for the miracle to come, for their wishes to come true at last. It is as if we were separated from these faces by an invisible veil, preventing us from penetrating to the depth of their inner souls. They carry their past and present locked up in their aloof selves.

In his first period, Ámos created a pure, idealised world much like the one for which he longed himself. It is a world in which space and time unfold in unison, and real experiences mingle with mythical, universal sentiments often accompanied by archetypal symbols.

In 1935, Ámos married Margit Anna, who became the permanent model for his paintings and drawings. The couple used a rented room as their studio. They shared a life of want and hardship, moving from room to room in the 1930s, but their love and faith in art and in one another always helped them rise above the abjection of poverty. As Margit Anna confided to the author in an interview taped on 5 January 1979:

We lived in dreadful destitution. We would take our modest breakfast of rolls and coffee at a milk bar on Károly Boulevard, then go home and work away like day labourers. The same way every day. We would paint with our backs turned to one another to avoid distraction. We had an especially hard time when all we had was an unheated room. At noon we would go to a nearby cafeteria for lunch, and we pocketed some extra bread for dinner. We walked everywhere to save the tram fare.

Ámos began to write his diary on 7 December 1935, in a school exercise book with a checked cover. The first sentences read:

I turned 28 today. I don’t know why I want to record the daily events of my life. I strive to express my thoughts in painting… Whatever I have achieved in the eyes of colleagues and people has been through my work. All I want is to settle down, attain spiritual balance, and continue along the path that now looms before me in almost perfect clarity, in the company of my chosen partner who stands by me with all her love and can make sense of my life – a life that has been hard but not disgruntled, and not without occasional moments of joy.

This diary serves as the most authentic mirror of the painter’s life, recounting small daily pleasures, worries, tribulations, episodes of inner torment, as well as containing sincere confessions of his creed as an artist. At times he would not write a single word for months, even years. At other times, he would grab a pen and put down his impressions and the events of his life for a quick succession of weeks on end. The diary clearly shows how painting filled his days perfectly.

All we do to achieve what we achieve is work – frankly, out of inner necessity, and without playing games. When we have some money we go out and buy some supplies. And if we manage to show some paintings, it is not because we have been pushy but because we have a decent portfolio and we work hard.

In 1936, Ámos participated in the 9th representative exhibition of the Munkácsy Guild at the National Salon. In July the same year, he was awarded the 250-pengő (the Hungarian currency at the time) prize by the Casino of Lipótváros District. Then, in autumn, he and his wife showed 38 paintings at the Group Exhibition No. CLXI hosted by the Ernst Museum. While being pestered by the cares and worries of the day, he became increasingly preoccupied with straining against the boundaries of reality, and with the arcane meaning of objects.

Dreamer, 1938

The painting entitled Before my Great- Grandmother’s Mirror (1935) no longer foregrounds the interior of the family home in Kálló. Instead, it condenses into a single space a visual memory and the fleeting moment of an afternoon in the small town. Beyond reflecting the pictures hanging on the opposite wall and the bed – made up with a high stack of pillows underneath the bedspread as was the custom in the countryside – the mirror is filled with blurred, floating images of the ancestors, representing the cohesive force of family across generations or, if you will, the eternal chain of being. The painting successfully challenges conventional unitary notions of time and space by conjuring up present and past simultaneously, literally on the same plane. This bears out the ars poetica Ámos articulated in one of his journal entries:

It does not suffice to paint an object, a figure or a landscape as just a motif. I believe it is the painter’s task to project, through his subjective vision, the soul of his themes, in other words the impact they have on their surroundings, as entities that somehow stay alive even in death.

Ámos is increasingly concerned with ways to project memory and dream in images. Indeed, the dream appears as the manifestation of desire throughout his work, in which the unconscious never disintegrates into discrete fragments. In these images, dream and reality merge to the effect of raising reality to the higher plane of the mythical. For Ámos, the dream offers a means to rid himself of the seemingly immutable facts of waking life, a way of casting off the shackles of reality. More than just the protagonist, the painter becomes the director of his dreams. Unlike surrealist painters, Ámos never for a moment disables consciousness and emotion which provide a link between associations. In his paintings, dreams always appear in real-life situations, enriching the gist of the tactile image by a wealth of intimated correspondences.

This complexity of the dream is treated extensively in his Dreamer (1938), which replaces modal unity by a concatenation of contradictory dream fragments. The dream here is no longer simply a projection of childhood fantasy or desire. The objects of the room may still convey the sense of a sheltered home, but the world outside as glimpsed through the window is now teeming with portentous signs as the painter enacts his own double, so to speak. The crown of thorns gracing the head of the imagined painter deep in slumber foreshadows the artist’s persecution and death anxiety.

September 1937 saw a perennial wish realised when, taking advantage of the promotional offers of the world fair, Ámos and his wife finally made a trip to Paris. Ámos absorbed the thrills of the famed metropolis with eager anticipation, and reported on them enthusiastically in his diary. Chief among these formative experiences was a meeting with Chagall. As he writes on 4 October 1937,

We have just come home from a visit with Chagall… We were at a loss for words in our joy at talking with him face to face, after locking him in our hearts through his paintings… He struck us as quite an endearing figure with his ruffled hair and wearing a reddish shirt over a yellow-black striped tricot, and gray wool pants. Smiling at us with that strange squint of his, he led us into a room filled with paintings, one just as wonderful as the next… He seemed very pleased that we brought along so many things to show him, as he directly set about leafing through the drawings… I saw his face light up in earnest admiration… He seemed genuinely impressed… “Sie müssen in Paris leben und arbeiten”, he said. He found a great deal of them impeccable. “You are still very young”, he continued, “but the inner feeling in these is excellent.” He also found the execution beyond reproach. He added that, if we came to Paris to work for an extended period, anything still missing would be revealed to us clearly.

Ámos was attracted to Chagall through his East European identity, upbringing, religion, and an introverted spirit of always seeking the truth which they also happened to share. Indeed, their works have numerous traits in common – not surprisingly, given the same resources that shaped their respective destinies, beliefs, artistic creeds and visions. Despite their different circumstances in life, the collective formative power of religion and the mystical experience of ordinary days and festivities, filled with prayer and rite, endowed them with very much the same moral fibre.

It follows from their mystical disposition that both approached the world from a vantage point that was essentially emotional. While the rest of the European avant- garde was immersed in experimenting with new forms of expression, Chagall and Ámos got busy fashioning a symbolic system of vision or a self-sufficient universe, in which the human condition gains a more profound dimension through the evocation of millennia-old archetypes of mutability.

Analogies between the two oeuvres are nowhere more apparent than in their shared emphasis on ancient symbolic motifs. Yet in Chagall’s paintings the pagan joy of life is suffused with introspection as man is dissolved in the euphoria of nature, whereas the gluttonous relish of life and explosive dynamism are alien to the sensibility of Ámos. While Chagall does not shirk from painting the apotheosis of inscrutable and unbridled love, the work of Ámos lacks the exuberant celebration of passion. He is possessed of a more bashful disposition, and given to hiding his innermost feelings from the outside.

Chagall knows how to play, and enjoys it, too. He likes to conjure up grotesque situations, and often portrays himself laughing at the follies of the world. By contrast, the work of Ámos is purely emotional in its conception, and clearly indicative of a spirit that seldom breaks free of the daily struggle for sheer survival, of the anxiety and torment of penury.

Among many other influences, Chagall’s style owes a great deal to Cubism. He never thinks twice about breaking up space; mixing the up and the down comes naturally to him. His paintings often link spaces harking back to the world of fairy tales, in which sensory experience no longer holds true and yields to a dynamic vision guided by the magic magnetism between the celestial and the terrestrial, the real and the surreal, in a mutual permeation of present, past and future. Ámos, too, forces the present dimension open, but without accelerating time or multiplying the moments that make it up. Instead, he seeks to charge up his soul and draw strength from a time conceived in the collective archetypal myth of the past.

Imre Ámos and Margit Anna spent three months in Paris. Upon their return to Hungary, Ámos turned with redoubled energy to the Hasidic lore of Kálló and his childhood religious memories. Rabbis lost in reverie, old vergers and ethically charged figures of the Old Testament became recurrent subjects in his paintings. The miracle-working tzadik, the wisdom of the elderly, the glowing candles of Friday evenings, and mother’s prayers are all entangled with the heat of the summer trapped in the narrow, sun-drenched streets and with the curious evanescent shadows vanishing into the twilight.

His Kabbalist (1938), too, shows us an enraptured face as he treads the streets, watched over by a circle of angels blowing silver trumpets. The mocking children are bitter recollections of the artist as a bullied child.

In his Dreaming Rabbi, the real blends with the surreal in the shared plane of the foreground. The blown-up images of the pelican and the fish, these two ancient symbols of Christ, are projected onto one another in a sort of palimpsest, attesting to how Ámos draws on universal myth beyond the specific cultural sphere of his own religion. At the same time, the painting shows us the funeral chapel of Eizek Taub, a simple sign smouldering in the red heat of memory.

After Paris, Ámos periodically sought refuge from assaults on his sheer existence in Szentendre outside Budapest which he had discovered back in 1935 on the invitation of Lajos Vajda. Although those early summer trips yielded a handful of watercolours and sketches in tempera, he had not discovered the intellectual riches of this picturesque small town on the Danube until 1938. Thereafter, he would return to Szentendre frequently, even between stints of labour service. In a diary entry dated 24 July 1939, he writes,

We have been sojourning here in Szentendre for five weeks now. It is an enchanting hamlet stock full of ready-made subjects for the painter. The ancient, narrow alleys, the old portals, and beautifully dilapidated churches fill the place with a peculiar atmosphere. Toward sundown, the hills are bathed in a surreal purple glow. Clear nights are especially beautiful, with the blinding light of the moon almost fluorescent on the weathered church walls. All my works conceived here somehow acquire a mystical charge.

In the townscapes he paints in Szentendre, the motifs are projected onto one another, the walls become transparent, and interiors merge with spaces in the open air. The forms are cast in brilliant colours and tones. Ámos transmutes Szentendre into a town of harmony and light with a yellow angel keeping vigil over the roofs.

As German troops march into Austria on 12 March 1938, Hitler annexes the country in a move known as the Anschluss, and follows up by seizing the Sudetenland in the wake of the Munich Agreement. Detached from politics by habit, Ámos comments on these developments in his diary as follows:

We experienced quite a few horrible days over the past few weeks. For the time being, the alarms have fallen silent and thoughts of an impending war now seem banished for a while. Or is it just a lull that conceals preparations for an even greater and more dreadful war? These apprehensions cannot be good for art.

Under the influence of events unfolding by the day, Ámos forecasts the looming historic cataclysm with intense force. His painting Synagogue (1938) shows the sepulchre of the wonder rabbi of Kálló in flames. The wise tzadik cries tears of blood over the perishing place of worship. A man fights in vain to put out the fire. Despite the appearance of a rooster sounding a shofar, all hope seems quenched by the red blaze.

May of the year 1938 saw the promulgation of the first Anti-Jewish Law, which restricted the ratio of Jews in the intellectual professions to 20 per cent.

It is so humiliating for us to be displaced from nearly all occupations. A great darkness has descended on people, as if they had succumbed to an infection that renders them inhumane. Anti-Semitism is being trumpeted as a miracle cure for all the ills of society, and although the leaders know full well this will never solve the burning issues, they stick their heads in the sand and hammer through law after law that drive people into the most dreadful destitution. They cast an entire group of people out of the hard-won stronghold of liberty, fraternity and equality.

The painter’s diary keeps track of the events bitterly, and reports on his spiritual torments and daily tribulations.

I have not done any work in weeks, and we live in utter uncertainty of the future. We have not had a prospective customer for months. For the moment we try to make ends meet – to get that bit of bacon for the morning and the evening – by painting grocer’s bottles with decorative motifs here and there, needless to say for a pittance.

In March 1939, the couple gave up their rented room, and Ámos’s uncle suspended their allowance. Ámos took up a job as a private tutor to earn a bare minimum of living. By then, he had found his opportunities to exhibit had shrunk as well.

A growing number of reviews, instead of engaging in real criticism, are talking about who is Jewish and who is not, whose wife is Jewish et cetera. As if the religion and faith of an artist did not consist of his art with which he serves and expresses his respect for humanity. These are adverse, turbulent times indeed… Once again, we have nearly come to the point of having to hide in catacombs to remain free to work.

Then, on 20 September 1939, he commits these lines to paper:

We no longer have a studio to work in. It has been days since I last brought myself to look at my boxed-up belongings. To think that I, the industrious craftsman that I am, should be relegated to sitting idly in a souterrain room so dark that I must blink my eyes in the blinding light whenever I venture outside, yet with no prospect of a way out in sight…

It was in such a tiny, obscure room that, in the spring of 1940, he drew and cut his 14 piece linocut series entitled Jewish Feasts. These works evoke the rituals of his faith, paying tribute to the joyous and mournful moments of history that had regulated the rhythm of life for millennia, providing the Jewish community with a means to remember its collective past. In turn, these traditions afford the artist a source of moral stamina to draw on during the years of persecution. These customs, in the representation of Ámos, express the faith of the simple man who observes and practices his religion daily. Each sheet foregrounds a male figure making a celebratory ritual gesture, drawn with dynamic contours.

In the summer of 1940, and for the last time, the couple spent three months in Szentendre on the right bank of the Danube, which by then had not escaped the signs of imminent war.

July 10, 1940. We are alerted by shrill commands and stampeding boots right in front of our door. Manci says it’s just the old soldiers on a drill outside. It’s hardly a soothing and inspiring milieu in which to get some work done. Ironically, I happen to be working on a painting in which the roof is burning over the head of an oblivious painter. The only thing reassuring in this picture is the figure of the angel lying on top of the roof and obviously not minding the flames. It is as if the painting had been inspired by the events transpiring at our door.

In The Painter before a House in Flames (1940), created under the influence of, or at least contemporaneously with, this disturbing experience, we see a burning house on the brink of collapse. The body of the artist working in the foreground is convulsed, his face disfigured with pain, while a protecting angel lies prone on the roof engulfed in flames. In marked contrast to the pastel hues of his early paintings, here the red of the fire is juxtaposed to the blue of water. The clash between cold and warm colours seems to push against the intrinsic cohesion of the composition.

During the months spent in Szentendre, Ámos created a series of powerful ink drawings in protest of the war (Tried and Found; Portrait of the Artist’s Wife – Muse II; Dark Times).

In September 1940, Ámos was served his first summons to labour service under company No. 201/32. He was enlisted in Nagykáta first, then reassigned to Balatonaliga. He sent his wife postcards from the camp, reporting on his physical and mental condition.

After a week of gruelling manual work in Aliga, on Sundays he would paint watercolours of the Balaton and the deserted gardens and streets around the lake, each capturing an unmediated impression of the landscape in light brushstrokes. The clouds in the sky are important motifs, as are the lakeshore promenades bathed in the golden glow of twilight or the blazing disc of the sun. Painting briefly alleviates his helpless hours building a railroad with sleepers. All of these lyrical images of Lake Balaton were born in the breaks during spells of forced march. “I am stretched on the ground after ‘a bit of walk’ which turned out to be twenty kilometres of punishing march… We marched on all day long, to a village and the one beyond and back, with a few moments of ‘flat on ground’ thrown in.”

Yellow Angel, 1939

Ámos endured these trying times with dogged discipline. On 12 January 1941, he recalls his tenure in the camps in the following words:

I returned from labour service on 13 December 1940, after spending nearly three months in hard physical labour. My fingers still hurt when I wake up in the morning. I may have developed rheumatism from pushing around cold wagons and hauling iron rails and sleepers. I am not a wimp. I was raised on farms and learned how to use a spade and shovel, if not to the extent I was expected to… But I was saddened by having to usurp the bread of the navvies and to abandon my palette and brushes. And I don’t think I would for a moment have served my country better by manual labour than by painting – although I have never backed out of work if work was to be done.

In January 1941, the couple rented a sunny room in a third-floor apartment on Hunyadi Square, which also served as a studio and allowed Ámos to resume work with redoubled force. It became clear that, for him, the only possible attitude in the face of a formidable Nazism lay in intellectual and artistic protest. He began to send prophetic warnings through his drawings and paintings, in a style that changed abruptly in the year the war broke out, shaped directly by the forces of history. It was in these calamitous times that he hit on the symbols as a primordial, mythical pool of resources to express the upheaval descending on his homeland and all of Europe. He uses these symbols for their terseness and unambiguity to deliver a testimony about the world, his self as an artist, the disintegration of moral values, the solitude, humiliations, anxieties and fears of man at the mercy of history – about the innermost disquiet of exile.

His arsenal of expression shifts as he begins to use forceful contours to delineate forms, as well as colours of burning red and intense blue, in stark contrast to the silvery pastel hues of his earlier work.

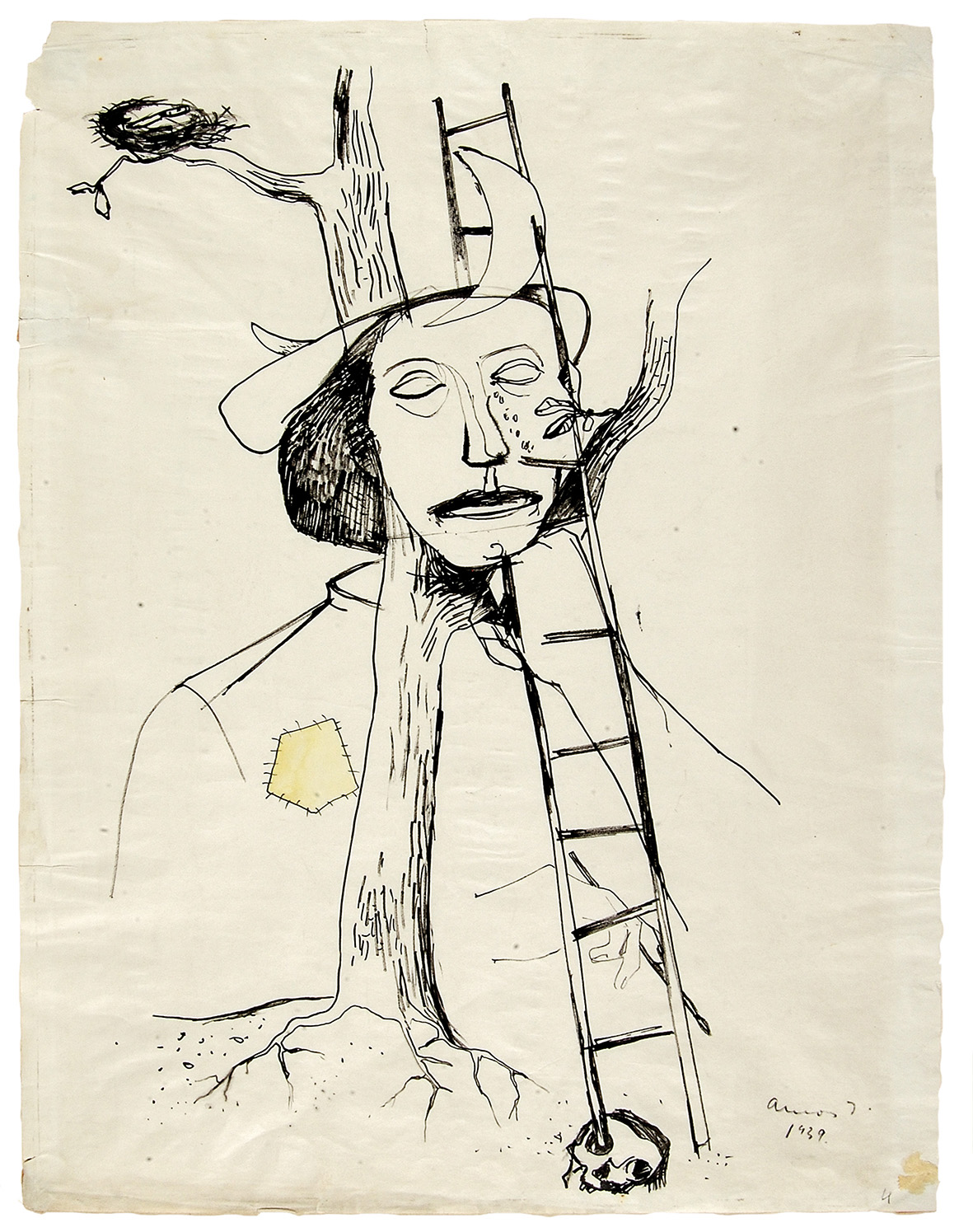

Yellow Patch, 1939

He relies more and more on the genre of the self-portrait as a means of revealing his true identity. He surrounds himself with symbolic motifs to emphasise his visionary, myth-making self, as in The Painter (1939). He paints twin portraits of himself and his wife as a memento of their love and belonging together. The figure of the angel features prominently as a leitmotif of his vision as a painter. “Behold, I send an Angel before thee, to keep thee in the way, and to bring thee into the place which I have prepared”, says God to Moses according to the Bible (Exodus 23:20). In the work of Ámos, the angel is privy to secrets and a guardian of humanity, extending protection to the life of the artist, as seen in Self-Portrait with an Angel (1938); The Angelic Hour (1938); Yellow Angel (1939); Angel with Bread (1940); The Painter and His Muse (1941); and The Two of Us (1941). Indeed, the angel is accorded a role in the painting of Ámos just as central as in the poetry of Miklós Radnóti, who shared his fate:

Until now all that dark and hidden rage lay in

my heart

like the brown seeds in the core of an apple, and

I knew

that an angel escorted and watched over me

with sword

in hand, walking behind me, and guarding me

in this troubled hour.

(Miklós Radnóti: Neither Memory, Nor Magic.

Translated by Gabor Barabas.)

Ámos’s burst of creativity was cut short in April by another conscription for labour service. For three months, he toiled in a road construction detachment assigned to the settlements of Aszód, Zombor, Stopár, Hercegszántó, Bezda, Bereg and Doroszló, until he was finally demobbed at the end of June.

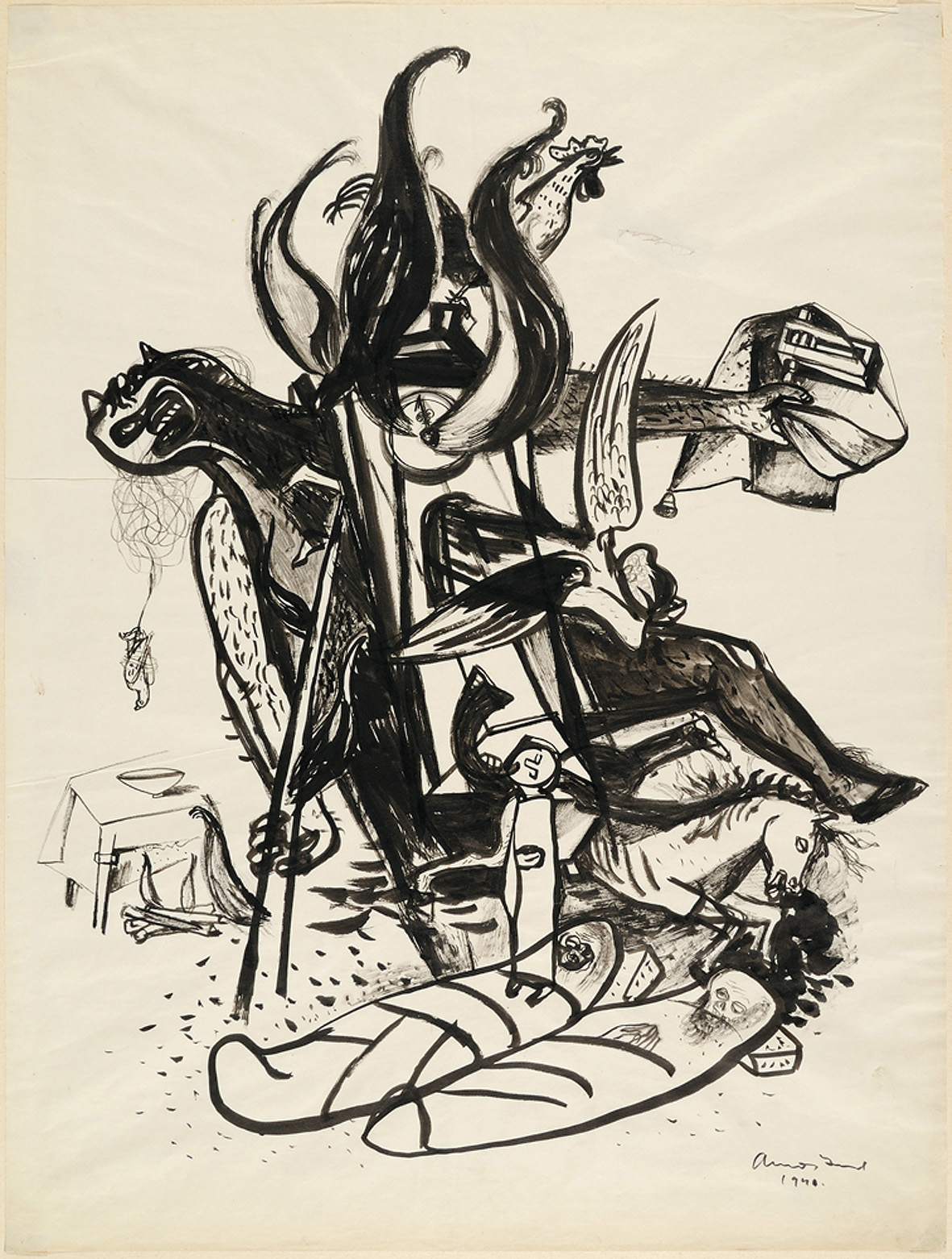

The summer finds him painting in Szentendre again. In the fall, he resumes work on his Dark Times. Completed over a period from 1938 to 1944, the paintings in the series articulate his nightmares of history with elemental force in an apocalyptic vision of wartime destruction and existential threat to humanity. The motif of the truncated, leafless tree surfaces over and over again as the tragic symbol of a world perished by violence – of the annihilation of life, goodness and knowledge, which the tree traditionally symbolises in Judeo-Christian tradition (War – sketch for a mural). Yet for Ámos, the desiccated tree always has a tiny sprouting sprig to signify hope in the coming of a new world.

In March 1942, Ámos and Anna showed a joint exhibition of drawings in their studio on Hunyadi Square. Soon afterwards, on the 18th of that month, Ámos received another draft call for labour service. His army corps was ordered to the Russian front in Ukraine, where he was to remain for a full fourteen months. He managed to survive the spiritual and physical ordeal, including a bout with near-fatal illness, by drawing on his sheer human faith and on the hope of returning home. While in Korosten, he contracted double pneumonia, then camp fever, a type of typhus. For days he lay between life and death on a straw bed in a Ukrainian peasant’s earthen-floored room. On 20 March, he wrote a letter to his wife but never mailed it.

I have been struggling with a vicious fever for days. All that marching has taken a toll on my feet, too… I pray daily to God to allow me to get home, kneel at my mother’s grave, and kiss my beloved’s cheeks… Sweetheart, you know my wishes. Sell my canvases one at a time, then organise a major retrospective exhibition, and then, should peace descend again, lead a serene spiritual life… Honey, I can barely hold this pencil I am writing with… Sweet love of mine, the two of us have been granted many a happy day by God, and I hope we will be still. Kisses, Imre.

He draws and pens poems on scraps of paper and white birch bark. A gendarme destroys his drawings.

At long last, on 24 June 1943, he is demobilised, and even succeeds in rescuing his poems and notes. Later he would paste in a grid-paper exercise book the 85 poems scribbled on scraps of paper barely a few square inches in size, along with the pencil drawings of the moribund he had sketched in a trembling hand. In August, he confides to his diary that

I will never forget those bitter days of hardship as we retreated through the weary pathless land in the depth of winter, in 35 to 40 degrees below zero… I am convinced it was the hand of God and the immense will to reunite with my wife that sustained me through the illness […].

I have a hard time finding myself again, staring at my own work as if it had been done by someone else. During the days of affliction I had a sort of epiphany which caused things I had hitherto held in high regard to shrink into insignificance, and vice versa: things I had previously ignored have now gained significance.

Ámos recalls his time on the Russian front in harrowing works. Memories of the horrors of war are presented in the drawings Refugees and Death, and in the watercolour Dying Horse. The helpless agony of the animal writhing in its death throes mounts a poignant protest against the conflagration, as the soldiers in retreat look back at the victim in horror.

Ámos continues to work feverishly in awareness of an utterly uncertain future, recording his appalling experiences, anxieties, torments of the soul and, at times, his hope in a better world to come. All the drawings and tempera paintings from this period, characterised by a terse economy of expression familiar from Hungarian folk ballads, speak in the voice of a humanist fearing for quintessential values yet trusting in the ultimate triumph of truth and peace. Forged from symbolic signs, the compositions do away with unity of space and time. The objects are divorced from their usual settings and, plunged in a new context, acquire new strata of meaning.

The artistic power of Ámos lies in the way he links his symbols together so that they mutually reinforce the meanings they embody. The association of seemingly remote motifs that do not appear in juxtaposition in real life creates a new aesthetic quality. The intellect is very deliberately united with emotion in the drawings. The painter jealously guards core human values and the heritage of the past, makes ample recourse to the Bible, and divines a future of freedom, all the while carrying on with his protest against violence with redoubled energy.

On 19 March 1944, Hitler’s troops march into Hungary, prompting Ámos to write in his diary two days later:

We are looking ahead to hard times, beset with adversity. War has come to Hungarian lands. We cannot know what will happen tomorrow. Let us place our trust in God and confront our destiny with a clear conscience. We have done our best for our country and our humanity. I am convinced that trials exist to purge the soul, and come what may, I am steady in the assurance that we have led sincere, honest lives, as artists and as man and woman. May God grant me the time to continue this diary in peace when all human souls have found complete rest.

On 12 April 1944, Ámos creates 12 large ink drawings of the Apocalypse, clearly projecting John’s vision on his age. John wrote his Book of Revelation around 95 AD,in exile on the island of Patmos, where he was disposed of by Emperor Dominitian in retaliation for his revolt against the persecution of Christians. John intended his work as an encouragement for the seven churches of Asia Minor to persevere in their faith. In his own cycle, Ámos identifies with John as a witness of conflagration plagued by the demons of history, and brings his own personal restlessness to the vision.

Dark Times, 1940

In the Apocalypse, Ámos heralds the coming of truth even as he intimates his own death in his diary, poems and letters.

The Jewish inhabitants of his hometown, including his uncle, aunt and half- siblings, are being deported as he works on illustrating the Bible. The fate of his kinfolk and friends in Kálló deals him a staggering blow. He evokes the image of Christ on the cross to convey his own suffering. In Terrible Times, he draws himself with hands clasped in prayer over the crown of thorns he wears on his head. His gaze is that of a man bidding an anguished farewell to life on earth.

At the end of May 1944, he is called up for labour service once again. This time, he is assigned to railroad construction in Jászberény and Szolnok. The camp postcards he sends to his wife, arriving with the pre-printed message “I am healthy and feel well”, divulge nothing about his actual situation. By then, those in labour service were not allowed to write in their own hand.

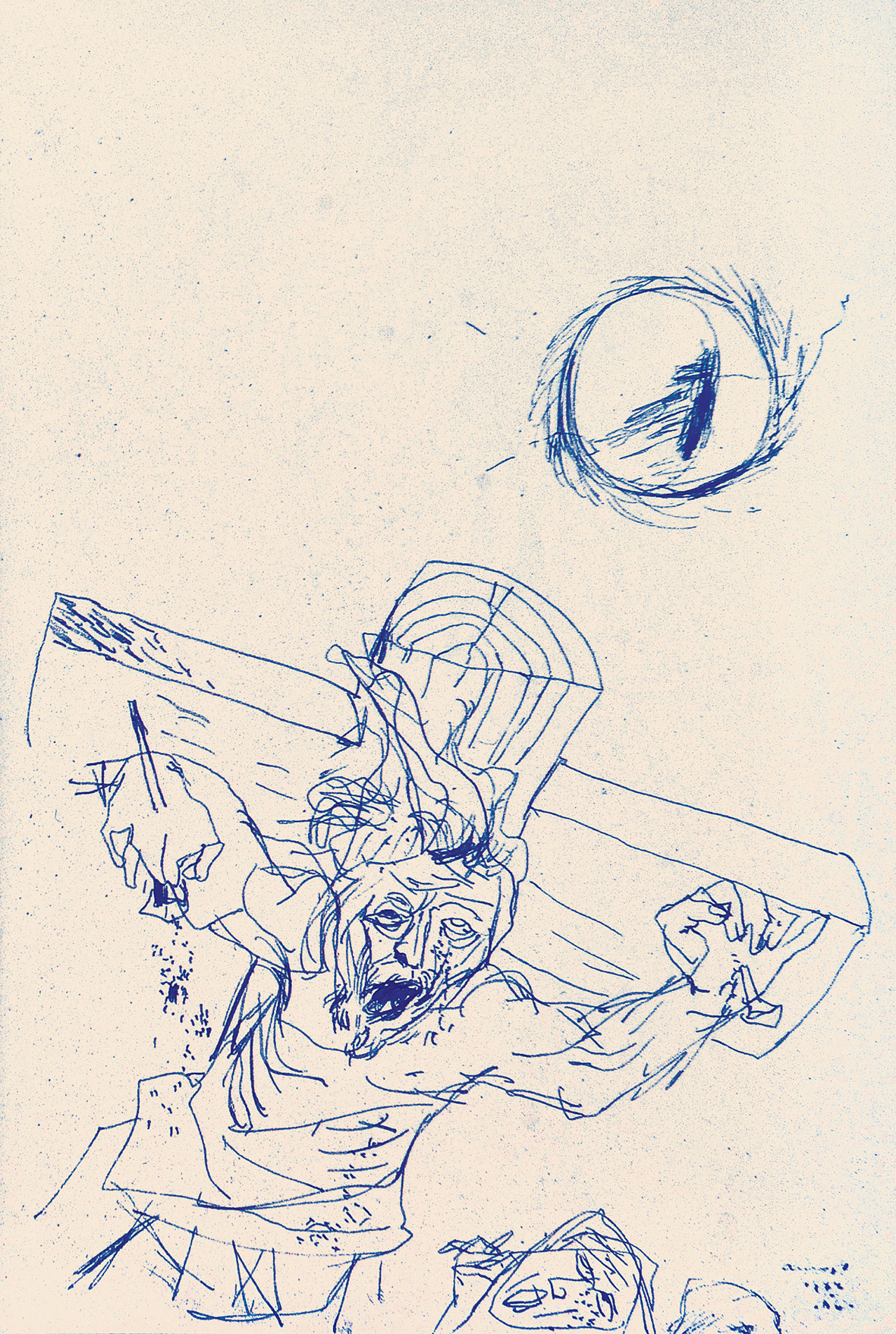

The Louse, Horseman of the Apocalypse, 1944

In August, he buys a 60-sheet spiral book, and fills 45 and a half pages of it with drawings in blue ink. Known as the Szolnok Sketchbook, this series marks the epilogue of the painter’s art and tenure on earth. In the midst of the humiliations of the lager, Ámos conjures up the tranquillity of the home and his love. These drawings, made in brief interludes between stretches of forced march, offer a moving confession about the bond between two human beings. The envisioned harmony, however, is interspersed with troubled, harrowing visions and images of war, as the artist attempts to come to terms with his destiny passing burning towns engulfed in the havoc wreaked by destruction. He turns to the figure of Jesus crucified between the two villains as a projection of his own suffering. The Biblical motif here is actualised quite literally by an axe smashed into the wood of the cross, which is inscribed with a swastika.

In October 1944, Ámos was relocated to Budapest. The day the radio blasted Szálasi’s taking of the oath was the day Margit Anna met her husband for the last time, in the courtyard of the barracks on Lehel Street. This was when he gave her the grid- paper book with the last pencil drawings which he had made in Szolnok.

Apocalypse I, 1944

Apocalypse I, 1944

Ámos then found himself on the Austrian border. The men of the company were made to sing the Hungarian anthem, then handed over to German command. The painter was never to return from Ohrdruf, the subcamp of Buchenwald. His death is a tragic memento that has been with us to this day.

Ámos kept “writing signs on the sky” to his last breath. Even in the face of imminent demise, he never for a moment ceased from trusting in the ability of man to attain purity and in the coming of a new era replenished in faith. The very last lines of his journal articulate in an extended rhetorical question the will of an artist in communion with the human race:

When shall man be brought to the state of living side by side with his fellows in genuine love, without violence and murder – without hatred, but holding the peace-loving in high regard and mending the ways of souls who have strayed from the true path under the sway of evil?

Translation by Péter Balikó Lengyel

Crucified Christ, 1944