19 January 2018

The Reformation in Hungary

“The peculiar paradox of the Reformation was its essentially ambiguous character,

for it was at once a conservative religious reaction and a radically libertarian revolution.”

Richard Tarnas: The Passion of the Western Mind

Having been reared by an Anglican mother and a Presbyterian (Church of Scotland) father, I have always considered Protestantism in Hungary a topic of particular fascination. When I first arrived here in the early 1980s, I was astonished to discover that around a third of the believing Magyars were Protestant, and of that third the overwhelming majority were Calvinist, or Református as they call it here. That astonishment was predicated on the erroneous assumption that the Counter-Reformation in the Habsburg Empire had swept all before it, leaving only the northern perimeter of Europe (Holland, Scandinavia, Northern Germany, Britain) as Protestant strongholds. When I later began writing about Austria, a further corrective was delivered to my preconceptions when I discovered that some 50 per cent of Austrians1 were Lutheran at the height of Protestantism’s brief influence in the mid-16th century, though the preponderance was most marked in Inner Austria (including Carniola which is roughly modern Slovenia).2 Under Emperor Maximilian II (ruled 1564–1576), who is thought by some historians to have been a crypto- Protestant, Vienna was 80 per cent converted to the new creed and even the Mayor was Lutheran.3 The decline of the Lutheran creed from the 1600s in Austria under Counter-Reformatory pressure was almost as rapid as its rise had been from the 1520s. In Hungary however, while the spread of Lutheranism had been equally rapid, it was quickly superseded by Calvinism on the Great Hungarian Plain and in Transylvania. Calvinism was a creed which proved durable and was in some ways peculiarly suited to the Magyar temperament. The extraordinary rapidity and intriguing particularity of these events were two of the puzzles to which I hoped this exhibition would provide a key, and I was not disappointed.

The untranslatable aphorism of the Hungarian title of the exhibition, Ige – Idők, combined the notions of the spoken or written Word of God and the “collective sense of time”; the English title, Grammar and Grace,4 focused on the relations of literary activities and church reform. The Curators5 constructed a chronological show that illuminated the idiosyncratic progress of the Reformation in Hungary through words and images. The approach was irenic and ecumenical, the stress being on the overall continuity in the Christian faith in Hungary as much as on conflict, and there was a marked absence of sectarianism. Thus there was a generous appreciation of how the early urgings for ecclesiastical reform often came from Catholics who saw the need for it (one thinks of reform-minded Franciscans or monks of other orders like András Horvát who turned Protestant or Catholic priests like Gál Huszár, who embraced Luther’s teaching and founded a printing press to disseminate it).

Moreover, in the special circumstances of Transylvania, the 16th century saw a remarkable degree of tolerance, until politics and religion became more bitterly entwined from 1600 onwards. As late as 1626 the great Transylvanian Prince Gábor Bethlen, a Calvinist himself, encouraged the printing of a translation of the Bible by a Jesuit priest called György Káldy, a work which was authoritative enough to influence Hungarian literary language. Although we are told that this competing Bible deepened the rivalry between Catholics and Protestants, Bethlen’s unusual gesture reflected the irenic spirit that had been apparent since the famous Edict of Torda (1568) and the subsequent edicts, which allowed great latitude to the competing Catholic and Protestant creeds of the region. One of the curators remarked to me that perhaps six to eight people were executed for heresy in 16th century Hungary, a tiny number compared with elsewhere. Some of them were most probably Anabaptists, but their execution was not the consequence of the laws against the “German heresy” (i.e. Lutheranism) of 1523 and 1525, but came about as a result of local political circumstances.6

By the early 17th century, however, this spirit of tolerance had been eroded by political struggle, and Bethlen himself involved Transylvania in the brutal Thirty Years War (his brother-in-law was Gustavus Adolphus of Sweden). Three Jesuit activists were martyred in Upper Hungary in 1619 and Bethlen spent long years fighting against the Catholic hegemony of the Habsburgs. All this was in stark contrast to the initially peaceful advance of Reformation in 16th century Hungary, a phenomenon that highlights the special conditions under which it took place. Before we examine what those might be, a few brief remarks about the development of that many-faceted phenomenon known as the Reformation may serve to provide a little background to its initially triumphal progress in Hungary’s central, northern and eastern provinces.

Simon Pictor: Calvary Altarpiece 1519, oil and tempera on wood, 323 x 218 cm, Nagyszeben (Sibiu). Overpainted in 1545 by Lutherans and repainted in the 18th century by Catholics

Simon Pictor: Calvary Altarpiece 1519, oil and tempera on wood, 323 x 218 cm, Nagyszeben (Sibiu). Overpainted in 1545 by Lutherans and repainted in the 18th century by Catholics

THE ORIGINS OF THE REFORMATION

Broadly speaking, the Reformation sprang from two intellectual and spiritual streams which sometimes mingled and sometimes flowed separately, though often in parallel. The Renaissance had engendered a new interest in ancient texts, both classical and Christian, and encouraged the application of rigorous scholarship to the same. Renaissance humanism was informed by a degree of scepticism and pragmatism, the writings of Erasmus of Rotterdam being particularly relevant in the case of Northern and Central Europe. On the other hand, separately from the largely secular influence of Renaissance thought, there had been a stream of apocalyptic reformism within Christianity itself dating back to the 14th century and usually driven by indignation at the abuses of ecclesiastical office, but also burgeoning into doctrinal disputes. Whereas the early Church of course often had violent arguments about liturgical and doctrinal matters (for example the Arian controversy), the linking of dissident views directly to the needs of the laity, thus inevitably endowing such views in due course with a political dimension, was an outstanding feature of proto-Protestantism.

An example of how reformism might become apocalyptic and even fanatical may be seen in the career of Girolamo Savonarola (1452–98), whose iconoclasm (aimed at the “pagan” culture of Italian Humanism), and brief establishment of a ”theocratic democracy” in Florence, presaged some of the less endearing features of Genevan Calvinism. For Central Europe however, a century before Savonarola the key influence (though chiefly in Bohemia and Moravia)7 was the English theologian and reformer John Wycliffe (c. 1330–1384). It was Wycliffe who originated what was to become the most revolutionary element of full-blooded Protestantism, namely the idea that “secular and ecclesiastical authority depended on grace and that therefore the clergy, if not in a state of grace, could lawfully be deprived of their endowments by the civil power”.8 The Czech reformer Jan Hus (c. 1372–1415) was influenced by Wycliffe, probably because the latter’s writings had become well-known in Bohemia following the marriage of the sister of Wenceslaus IV to Richard II of England. The legacy of both Wycliffe and Hus was the fierce activism of their followers after their deaths, the Wycliffites in England (called Lollards) and the Hussites becoming ever more aggressively militant. The Hussite attacks on Upper and Lower Austria (but also Upper Hungary) were legendary for their violence and may be compared with the later similar attacks on eastern Austria by the mainly Calvinist Magyar irregulars known as kuruc.

Hans Kemmer (1495–1561), Law and Redemption. Oil on wood, Museum of Fine Arts, Budapest

.jpg)

Epitaphium commissioned by Jób Zmeskál for his wife Petronella Gelethfy. Jacob Khuen jr., Besztercebánya/Neusohl/Banská Bystrica, Slovakia, 1600, tempera on wood, 230 x 197 cm, Roman Catholic Church in Berzevice

In purely religious terms, the most important aspect of proto-Protestantism carried over into the creeds of Luther and Calvin was the central importance placed upon the Bible, and this is one of the matters extremely well explained by the exhibition and highlighted in respect of Hungary. As is well known, publishing the Bible in the vernacular, though primarily designed so that it could be read in churches, soon also put it into the hands of the literate layman. On the one hand it established “the culture of the word” which supplanted religious images that exploited “the culture of the senses” to convey the divine message; on the other, insofar as it initiated private study of the Bible beyond the immediate control of the clergy, it “democratised” religion, providing a potentially dissident alternative to a rigorously hierarchical Catholic Church that insisted on its exclusive role as intermediary between the believer and his God. Luther’s German translation of the Bible had been published in more than 400 complete or partial editions by his death in 1546, and the first complete New Testament in Hungarian was János Sylvester’s edition (based on the Greek text) which was published in Sárvár in 1541. However the writer and printer Gáspár Heltai and others then published a seven-volume Hungarian Bible on Lutheran principles, meaning that theological considerations took precedence over philological ones. This was perhaps an early sign that it was necessary to guard against sectarian deviation, which indeed rapidly became a feature of Protestantism.

THE REFORMATION COMES TO HUNGARY

The first wave of Reformation in Hungary followed Luther’s pinning of 95 theses to the door of the Wittenberg church (1517) in only a few years. Since reformatory discourse at this time was of course in German, it naturally arrived first in the German communities of Hungary, which were many and substantial. From the German-speaking inhabitants of Buda, it spread through the mining towns and the Szepesség of Upper Hungary (Felvidék, today Slovakia) and even to Sopron and Pozsony (today Bratislava). Finally it reached the Saxon population of Transylvania. These generally literate German merchants, craftsmen and mining engineers were already susceptible to the Erasmian devotio moderna and Christian humanism which included among its followers the tutor to the young Jagiello King of Hungary Louis II, the court chaplain to the latter’s widow, Queen Maria, as well as her secretary and later Archbishop of Esztergom, Miklós Oláh. The philological discipline of Erasmus’s New Testament translation initially served as a model for Hungarian translation into the vernacular. As István Bitskey writes: “Humanistic philology blossomed in the work of the Erasmian Bible translators in Hungary; their work opened the way to the further development of literature and scholarship in the vernacular.”9

Exhibition room with a small organ from the Lutheran church of Torvaj, 1742

The reason why the Reformation discourse found such a ready hearing in Hungary lies, however, as much in geopolitical and local political factors as it does in an altered state of mind stemming from propagation and polemic. The above-mentioned Louis (Lajos) II lost his life in the second great disaster of Hungarian history10 at the battle against the Ottomans at Mohács in 1526. As the exhibition reminds us, not only the flower of the Hungarian nobility was wiped out at this battle, but also most of the great lords of the Church (six bishops and an archbishop lost their lives). Since the time of Matthias Corvinus the higher clergy had become increasingly secularised to the point that many church dignitaries had largely ceased to carry out ecclesiastical duties, a point underlined by their presence on the battlefield. Their eradication degraded the ecclesia docens even further. As the wall text poignantly puts it: “The already orphaned flock was thus left shepherdless for good.” This spiritual and administrative vacuum was filled by the new teachings, which stressed the unmediated responsibility of the individual for his duty to God (a reaction against the corrupt sale of indulgences) and the need to move beyond the believer’s devout but uncomprehending absorption in the Latin mass.

THE SPREAD OF CALVINISM

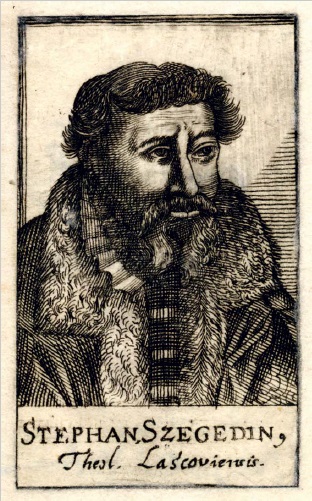

Almost all existing histories of Hungary provide vague or unsatisfactory explanations for the rapid success of Calvinism in Hungary. The exhibition provides an ingenious, if partial, answer, namely that when Hungarian students, the main transmitters of Protestantism on the ground, went to study theology in Wittenberg, many of them had no German and therefore attended the lectures of Luther’s colleague Philipp Melanchthon (1497–1560), who discoursed in Latin. The latter was more open than Luther to Zwinglian and Calvinist doctrines of the Eucharist and in his later life was regarded as espousing “crypto-Calvinism”. István Szegedi Kis (1505–1572), an eminent Hungarian theologian, was a disciple of Melanchthon and spread Calvinism in the market towns of the Alföld (the Great Hungarian Plain), which was to become a stronghold of the faith. However the career of the scholar Péter Bornemisza (1538–1584), who was strongly influenced by Melanchthon and became a Lutheran bishop, suggests that the influence of the latter was more diverse that this theory implies.

It seems equally likely that the Calvinist theories of predestination appealed to the Magyar temperament. The exhibition points out that many Hungarians believed that the catastrophe of Mohács was the judgement of God on a sinful nation where the corrupted Church had failed the people in its hour of need; that is, failed to provide the intercession with the Almighty and the Virgin Mary on which its authority rested. Huddled in the market-towns of the Great Plain into which they had been driven by the Turks, the nyakas (obdurate) Magyars nurtured a philosophy of stoic survivalism while pondering the notion that God has called us (to salvation) “not according to our works, but according to His own purpose and grace” (Timothy 1:9). The Hungarians were a chosen nation with a state- building mission, but it seemed they had been chosen to suffer. Not for nothing did their Catholic, Habsburg-loyal opponents refer with disgust to Calvinism as “the Magyar creed”.

CULTIVATING THE “GRAMMAR”

It was indeed a Calvinist pastor, Gáspár Károli (1529?–1592?), who published the first full Hungarian translation of the Bible, the famous Vizsoly Bible of 1590, which had the same authoritative impact on literary Hungarian, and thus on Hungarian identity, as the great Authorised Version (1611), commissioned in England by James VI and I, had on English literary expression and identity. Yet Károli too, like Luther and Calvin before him, was cautious about opening the floodgates to sectarian eccentricity, writing in his Preface to the Bible: “Only Christ can illuminate the meaning of scripture”, a near echo of Luther’s remark about his own translation that “grammatica must follow the sense of the Holy Spirit”.

The idea of Reform was not to overturn the established faith but to return it to its pristine origins. Luther had trouble with his former protégé, the charismatic proto-Communist Thomas Müntzer, who led a peasants’ rebellion; and Calvin had a hand in the burning of Michael Servetus for heresy. Bertrand Russell has observed that it is the fate of revolutionaries to found new orthodoxies; but in the case of the Reformation leaders it was their fate to become by default the spiritual and intellectual transformers of society through their conservative defence of the true faith as it was before it became corrupted by a secularised church and corrupt papacy. Moreover, there has often been a certain diversity and ambivalence about Protestant theology compared to the centralised authoritarian dogmas of Roman Catholicism. To quote Richard Tarnas again: “The first premise of Luther’s reform – the priesthood of all believers and the authority of the individual conscience in the interpretation of the scripture – necessarily undercut the enduring success of any efforts to enforce new orthodoxies.”11

The exhibition makes the point that “in Europe, the success of the [Protestant] reforms was due to political intervention; in Hungary, it was the lack of such intervention that enabled the new teachings to be freely disseminated”. The Transylvanian princes, many of them converts to Protestantism, had a delicate balance to maintain: they could not afford to upset the Turks, under whose suzerainty they were after the fall of Buda in 1541, and who would also be happy to see destabilising dissension among the infidels. On the other hand the Habsburgs, with their dynastic claim to Hungary and Counter-Reformatory zeal, were an ever-looming menace. They had their Catholic and Protestant populations, but the territory also became home to many who had fled Western Europe after persecution and embraced creeds such as Anabaptism and Unitarianism. The latter was particularly influential in Transylvania under its able leader Ferenc Dávid, formerly a Calvinist bishop in Kolozsvár (today Cluj), and became one of the four “accepted” denominations (recepta religio),12 whose freedoms were enshrined in the celebrated Edict of Torda (1568) already mentioned.

Modern historians go out of their way to de-romanticise the Edict, the relatively narrow scope of which was gradually extended over the years, but the fact remains that it was “unparalleled in the entire history of the Reformation in Europe”.13 It decreed that priests and ministers were free to preach the Gospel according to their own interpretation, which the community might accept or invite another preacher. Persecution and forcible conversion were ruled out. Although the Edict did not cover the Orthodox Romanians, Jews or Muslims, the Orthodox Church was later officially recognised when Gábor Báthory (1608–1613) exempted the Orthodox priests from feudal obligations and secured their right to free movement. His successor, Gábor Bethlen (1613–1629), confirmed Báthory’s decree in 1614, as well as allowing the Jesuits to return to Transylvania. Sanctions against Jews were moderated, and they were no longer obliged to wear the Star of David. In addition some two hundred of the much persecuted Hutterites (Anabaptists) were settled in the principality and later Sabbatarians were given refuge. They found much favour among the Hungarian Szeklers, although they were eventually (1638) banned from preaching by Prince György Rákóczi I. In an increasingly multi-denominational Transylvania it was however Calvinism that became dominant, not least because of its adoption by much of the aristocracy and several of the most politically able Princes.

Palatine György Thurzó on the Catafalc, Leipnik. Václav Svoboda, 1621, oil on canvas, 105 x 228 cm. Alsókubin (Dolný Kubín), Múzeum Pavol Országh Hviezdoslav, Slovakia

Palatine György Thurzó on the Catafalc, Leipnik. Václav Svoboda, 1621, oil on canvas, 105 x 228 cm. Alsókubin (Dolný Kubín), Múzeum Pavol Országh Hviezdoslav, Slovakia

THE IMPACT OF THE COUNTER-REFORMATION

Although the Princes of Transylvania, some Catholic, some Protestant, presided over a system of recognised religions, the exhibition warns that “this development should not be thought of as religious tolerance in the modern sense; rather, it was cooperation under duress. Certain ‘free thinkers’ of the radical Reformation did, however, envisage freedom of speech and opinion in a way which would later be accepted in the Age of Enlightenment.” The Habsburg court could not consider enforcing measures against religious freedom until the Turks had been beaten, but even then had to exercise caution because the local nobility was still largely Protestant. Even two of the Palatines of the truncated crescent of the Kingdom of Hungary that included western Pannonia and Upper Hungary were Lutheran. István Illésházy was only in office for a year (1608–1609), but he and his formidable wife Kata Pálffy were notable patrons of Reformation culture. He financed the printing of On the True Church of his nephew Tamás Esterházy, who studied at the University of Wittenberg. A fascinating aspect of the age was that confessional differences did not count much between the members of the Hungarian aristocracy: Catholics and Lutherans made alliances and marriages between each other.14 The Palatine who followed Illésházy, György Thurzó (1557–1616) was also Lutheran and likewise an important patron of the arts and a shrewd politician who sought to reconcile the interests of the Transylvanian Princes with those of the Habsburgs. He was a benevolent influence as Palatine between 1609 and 1616.

István Szegedi Kis, the leading Hungarian reformer turning toward the Helvetic Reformation, portrayed in his European bestseller Loci Communes [Theological Commonplaces], first published in 1585 in Basel by his student Máté Skaricza, the author of his biography

Beyond the patronage of the aristocracy there was also the independence built up by a burgher class, most obviously in the Calvinist stronghold of Debrecen. The latter is vividly described here as the city that “considered itself a Christian republic in the Calvinist sense and Magyar Jerusalem, which called itself Christianopolis and Theopolis on the title pages of some of its publications”. For two centuries this rich market town on the eastern edge of the Great Plain was a homogeneously Hungarian, Reformed, and virtually independent Christian republic. Its Genevan style religious governance lasted until the mid-18th century.

By the turn of the 17th century, however, Protestant governance had become identified with national resistance to the lawful, but disputed rule of the Habsburgs, who, for their part, were now gearing up for the Counter-Reformation employed as an instrument of imperial hegemony. Adherents of the Bocskai Rebellion (1604–1606) claimed to be defending the ancient freedoms of the country, into which were folded new religious freedoms that stemmed from political self-determination. István Bocskai did achieve recognition of the Lutheran and Reformed denominations by the Treaty of Vienna (1606), which concluded the “rebellion”. “All this”, the exhibition tells us, “wrought a fundamental change in the Protestant attitude to politics. The primarily biblical Protestant interpretation of politics, which saw Bocskai as a Moses for the Magyars, was supplemented with elements of the medieval constitutional-corporative traditions. There appeared a Protestant concept of the nation, interpreted more politically than merely spiritually and extended to broader social groups. The interested parties now gave voice to these new ideas in the political debates in print.” Disputation with the Catholics was itself a stimulus to the “culture of the word”. The most famous example of this was the preaching and writings of the inspirational Counter-Reformatory advocate Péter Pázmány (1570–1637), Archbishop of Esztergom and a great educator who founded the Jesuit University at Nagyszombat (Trnava, Slovakia) in Felvidék and laid the basis for the expansion of Baroque literary culture in Hungary. He confronted Protestantism head on by writing his powerful Catholic apologia (1613) in the vernacular, Az isteni igazságra vezérlő Kalauz (The Guide to Divine Truth). The Hungarian language gained a new dimension by the passionate argumentation of this great stylist, who indeed came originally from a Protestant family.

This fertility of disputation serves as a prelude to the final rooms of the show which document (somewhat sparsely) the later achievements of Protestant Hungary as it battled first the Counter-Reformation, then Absolutism, emerging in the 19th and 20th century as the rich fount of Hungarian literature that counted among its adherents such writers as Hungary’s national poet Sándor Petőfi, János Arany, Mór Jókai, Endre Ady, Zsigmond Móricz and Gyula Illyés (on his mother’s side). Some of Hungary’s best known politicians (Lajos Kossuth, the dour Calvinists Kálmán Tisza and his son István, as well as Miklós Horthy) were Protestant; also the discoverer of the properties of Vitamin C (Albert Szent-Györgyi), together with other scientists, architects, engineers, educationalists and painters, not to mention the great Béla Bartók himself.15 The final section reminds us of the Protestant notion of “work that was honoured, and pleasing to God, [which] provided the basis for economic development”, and “was confirmed by the attitude of the Swiss Reformation to predestination. According to Reformation doctrine … the hard work concomitant to a puritanical lifestyle and its result, material wealth, makes visible God’s blessing, and the destination of the person for salvation.” Max Weber’s controversial linking of Protestantism to the rise of capitalism16 can be glimpsed here, echoing the parable of the talents in the New Testament. “Trade and financial enrichment became an honourable employment due to the view of Calvin and especially the puritans.” This view also had an effect on the German language, as the exhibition points out: “Luther’s literary work enriched German with new expressions. One such word is Beruf, which means vocation [in Hungarian, hivatás]. Every job can be a vocation. In the kingdom of God, the servant girl works conscientiously just like the priest, the monk, or the prince.” (One finds the same sentiment in the Welsh poet George Herbert’s The Elixir (1633): “Who sweeps a room as for Thy laws / Makes that and the action fine.”)

These nostrums of diligence, self-discipline and self-reliance were inculcated through the Protestant school system that spread throughout Reformation Hungary, and even into the Turkish occupied zone (Tolna, Kecskemét). Notable was the school at Sárospatak founded in the 1550s where the great educationist Janus Comenius (Jan Amos Komenský) taught between 1650 and 1654. His pedagogy emphasised the development of character on Christian lines, while his approach to religious reform was irenic and universalist (“pansophism”), notwithstanding his background as a minister for the Bohemian Brethren and the persecution he had suffered at the hands of Catholicism. A computerised display at the exhibition shows the distribution of Hungarian reformed schools through different periods, coming to an abrupt implosion with the Treaty of Trianon at the end of the First World War, when 17 out of 25 grammar schools were lost to the successor states. This, followed by the Communist attack on religious schooling, marked the decline of what was arguably the greatest individual contribution of the Reformation to Hungarian society.

Wine cup for communion from Debrecen, late 17th century, renewed in 1791. Silver, partly gilded, embossed, chased, engraved, h.: 28 cm. The Theological and College Library of the Transtibiscan Reformed Church District, Debrecen

Wine cup for communion from Debrecen, late 17th century, renewed in 1791. Silver, partly gilded, embossed, chased, engraved, h.: 28 cm. The Theological and College Library of the Transtibiscan Reformed Church District, Debrecen

THE WILL TO SURVIVE

It was in Debrecen that the (second) “Moses” of the Hungarian nation, the Lutheran Lajos Kossuth, presided over the short-lived dethronement of the Habsburgs, the apotheosis of the centuries-long struggle between the “Magyar creed” and the Habsburg “alliance between throne and altar” of the Counter-Reformation. Much more could be said about the exhibition’s excellent illumination of the nexus between Protestant spirituality and political ideas, liturgical, iconographic and architectural aspects of those wonderful Transylvanian and Alföld churches; and last but not least, the differing mentality of the largely Protestant kuruc Magyars and the largely Catholic labancs. Not mentioned here is the most extreme manifestation of kurucism when the Transylvanian Prince Imre Thököly actually joined the Turkish army besieging Vienna in 1683, an act of foolhardy opportunism that the Habsburgs were slow to forget.

Wine tankard for communion from Debrecen. Donated by György Rákóczi I’s captain Dávid Zólyomi, 1631, silver, partly gilded, embossed, chased, engraved, h.: 41 cm, diam. of foot: 21 cm, diam. of lid: 13 cm. Great Reformed Church, Debrecen

Bryan Cartledge entitles his masterly history of Hungary The Will To Survive, a will interpreted differently according to whether you accommodated yourself to Habsburg rule with attendant rewards or doggedly stuck to your religion and oppositional stance in the fastnesses of the Alföld and Transylvania. Those choosing to do the latter certainly paid a price for their stubborn resistance. Cardinal Kollonitsch, chief adviser to the court of Leopold I, who hated Protestants as much as he hated Jews and sent 42 of their pastors to the Neapolitan galleys in 1675, articulated what they were up against in a bloodcurdling threat: “First I will make the Hungarians beggars, then I will make them Catholics, and finally I will make them Germans.”

Kollonitsch’s dream was not fulfilled and the Hungarians remained Hungarians. Instead, nearly four hundred years later, the Polish Pope John Paul II visited Debrecen, the “Calvinist Rome”. On 18 August 1991 he laid a wreath at the monument to the 42 persecuted Protestant pastors as a symbol of reconciliation. He then made a moving address to an ecumenical congress held in the great church to an audience of Catholics, Lutherans, Calvinists and even representatives of Hungary’s tiny Orthodox community.

Pulpit crown from the “Old” Reformed Church in Hódmezővásárhely, 1732. Tempera, wood, Tornyai János Museum and Cultural Centre, Hódmezővásárhely

The historic and analytical part of the exhibition too ends on a note of reconciliation that features the famous Edict of Tolerance issued by Emperor Joseph II in 1782. Maria Theresa, Joseph’s mother, had been educated by Jesuits and was both violently anti-Semitic and aggressively hostile to Protestants for most of her reign. As late as 1778, in her patent religio aimed at the peasantry, she banned Lutheran books, laid down that only Catholics could marry, and that only persons certified as being members of a Catholic congregation could buy property. Catholic apostates faced even more drastic discouragement, including flogging and transportation. However her attitude was vigorously opposed by her co- regent and son, who remarked that such measures were “unjust, impious, impossible, harmful and ridiculous”, threatening to resign if they were not revoked.17

The Protestants of Hungary endured years of “Babylonian captivity” when the peasants were obliged to conform outwardly to Catholicism while privately adhering to their Calvinist or Lutheran beliefs (hence the name “secret Protestants”). Catholic zealots pressed the theory that Hungary was the regnum Marianum, which referenced the tradition that King Saint Stephen had placed the country under the protection of the Virgin Mary. Nevertheless Lutherans and Calvinists survived until Joseph’s Edict laid the foundation for the more pluralistic approach to religious conviction of the Enlightenment. It marked the end of more than two and a half centuries of struggle and persecution.

Notes:

1 ”Austrians” is modern shorthand for the inhabitants of the Habsburg Hereditary Lands.

2 See: Peter Vodopivec: “Reformation and Counter-Reformation in Inner Austria: A Crossroads of German and Italian Influences”, in: Frontiers of Faith: Religious Exchange and the Constitution of Religious Identities 1400–1750, eds. Eszter Andor and István György Tóth (Central European University European Science Foundation, Budapest 2001), pp. 203 following.

3 Estimates put the number of Protestants in Hungary in the same period at about the same percentage.

4 The title was suggested by a book by Brian Cummings, who kindly let the curators adopt it for the exhibition.

5 Curators: Dr Erika Kiss (Hungarian National Museum), Dr Botond Gáborjáni Szabó (Museum of the Reformed College of Debrecen), Dr Zsuzsa Fogarasi (Ráday Museum of the Reformed Church Diocese of Dunamellék), Dr Béla László Harmati (Lutheran Museum), Dr Botond Kertész (Lutheran Museum), Zsuzsa Zászkaliczky (Lutheran Museum), Márton Zászkaliczky (MTA BTK ITI, Institute for Literary Studies of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences), Dr János Heltai (National Széchenyi Library). Design: Tibor Somlai. A studio exhibition titled Protestant Ways of Life in the 20th Century is connected to the Grammar and Grace exhibition, organised by Gyula Hosszú.

6 Church historian Zoltán Csepregi has shown that these executions were not directly connected to laws passed by the Hungarian nobles at the diet of Rákos in 1523 and 1525 (“All the Lutherans should be burnt” – “Lutherani omnes comburantur”, 1525), which targeted mainly German courtiers who were believed to be Lutherans. The laws were withdrawn in 1526, but the Decreta of 1584, “smuggled them back” into the collective memory of the Protestants, transforming them into Protestant martyrology instead of actual executions.

7 The Hungarian Hussites were expelled from Transylvania in the 1430s. The famous Black Army of mercenaries deployed by King Matthias Corvinus had included a large number of Hussites.

8 The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church, eds. F. L. Cross and E.A. Livingstone, Oxford University Press, Third Edition, 1997, p. 1769.

9 István Bitskey: “Spiritual Life in the Early Modern Age”, in: A Cultural History of Hungary: From the Beginnings to the Eighteenth Century, ed. László Kósa (Corvina, 1999), p. 241.

10 The first major disaster affecting the integrity of the country was the Tatar (Mongol) invasion of 1241–43. The third great disaster was the Treaty of Trianon following the First World War.

11 Richard Tarnas: The Passion of the Western Mind: Understanding the Ideas that Have Shaped Our World View (Pimlico, 2010), p. 240.

12 The four “accepted” faiths were eventually: Catholicism, Lutheranism, Calvinism and Unitarianism. In 1570 Sabbatarians fled Germany for Transylvania and were sheltered by the Unitarians, although their German persecutors had been Calvinist.

13 István Bitskey: op. cit., p. 246.

14 Géza Pálffy: “Pozsony megyéből a Magyar Királyság élére. Karrier lehetőségek a Magyar arisztokráciában a 16–17. század fordulóján” [From Pozsony County to the top of the Hungarian Kingdom. Possible carriers for the Hungarian aristocracy at the turn of the 16th and the 17th centuries]. (“Az Esterházy, a Pálffy és az Illésházy család felemelkedése” [The rise of the Esterházy, Pálffy and Illésházy families].) Századok 143. (2009), No 4, pp. 853–882.

15 He converted from Catholicism to Unitarianism.

16 Max Weber: The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism (in German Die protestantische Ethik und der Geist des Kapitalismus). Begun as a series of essays, the original German text was composed in 1904 and 1905, and was translated into English by the American sociologist Talcott Parsons in 1930.

17 See inter alia Jonathan Israel: Democratic Enlightenment: Philosophy, Revolution and Human Rights 1750–1790 (Oxford University Press, 2013), p. 283.