19 January 2018

The Reformation Today

What, if anything, will shape the possible future of Hungary and the Hungarians? Will we, Protestants and Catholics, be a blessing for a future Hungary? The question is whether all of those who have something of value that only they know and they know best can add that value to the common effort, and the common good.

All of them? Yes. This of course includes all Hungarian citizens, regardless of their background. All of them: meaning the various communities, the self-organised civic world and the national minorities living in Hungary. It includes both the middle class and the aristocracy in the true sense of the word.

Will they bring to the community everything they owe to this nation? It is also crucial that those presently living in deep poverty (including, but not limited to the Hungarian Roma) will be able to make further contributions to the common good. That we can create the necessary conditions to help them and that they will want to contribute. Will they too indeed add that what they owe this country?

Should these things fail to add up, there will be no common ascension – as we, Protestants say – and there will be no blessing on the future of Hungary. It may even happen – as happened before in previous decades – that various achievements will cancel out one another. It may even happen that all the individual and community strivings of the country will not add up, but rather turn against one another. In order for all the values of this country to add up and foster positive results, there has to be a “centre”. A centre that can be both a starting and a reference point, a goal to strive for.

In the language of politics, there should be some kind of consensus, a common understanding about what is valuable in our past and what future we intend to build for the country upon those values. There are plenty of values in our past, our present and in ourselves, but these only seem to be individual components, scattered parts of a mosaic that do not assemble into a coherent picture.

How can these values be relevant not just for the parts, but also for the whole? How should they influence not only the areas they are thought to be relevant for? Furthermore, the totality of these parts is not the “whole”. So we should ask ourselves time and again: how does the whole come into being?

How can something created in a different cultural, social or faith context be relevant to those outside of it? Who can and should offer what he creates to the entire community?

This raises the next question: who speaks for everybody, who can address everybody and who can speak to the whole human being? Not only to the employees, the consumers of culture, the ill and the healthy, not just the youth or the elderly, not only those with faith, but to the entire human being?

Where are the people, where are the communities that can achieve that? This question calls to mind the Christian heritage of our society. I think of those who will never accept that the “whole” should be divided, torn into pieces, and everybody should only be occupied with the parts they deem important for them.

The Christian community is the one that does not accept this division of the reality and the human being. I did not mention the Christian community with regard to achievements, because they are the ones who should speak and act not only in the name of but also for the entirety. They are the ones who should always have relevance beyond themselves.

This, of course, could also be misunderstood from the outside. Upon hearing the word “mission”, those outside the Christian communities can easily think that churches are again claiming something, demand the right to interfere, want to change people. “The church should concern itself with the soul of its members and leave the rest to politicians, economic agents, the entertainment industry and who knows whom else.” This is how they retort.

When hearing these summons we Protestant Christians tend to resort to a false apology. We try to present what the nation and the country would have become without us. And we can indeed be proud when asking: where would the Hungarian nation be without Protestantism? What would have become of the nation without Christianity? What would Hungarian culture be like without the wonderful Protestant church music and many other things? Without the admirable Christian works of art? What kind of education would we have without the Debrecen College or the Budapest–Fasori Lutheran Secondary School? How many fewer Nobel-laureates would we have in Hungary! What would the economy be like without at least the remnants of the Protestant work ethic, according to which one can simultaneously work for the benefit of man and God? What would happen to the destitute without Christian charity? Without the organised charities? What would happen to the suffering if we left them alone? And, most importantly, what would the Hungarian language be like, had Gáspár Károli not translated the Bible in the 16th century? Would it not be a great loss?

But this is not why we are needed. It is important to realise that we Christians, Protestants, are not needed because all the above would be missing from the “whole” without us. These are but the consequences of something far more important.

We could also say that these actions and achievements are but the carriers of the message. This stands for everything we do in the fields of culture, education, social assistance and elsewhere. Their primary mission is first to lead others to the message and then to become the consequences of that message. A Church or a church community that does not transcend its own existence and achievements only exists for itself and is not a real church community.

The Church and the Christian community is not the centre in itself, but rather endeavours to point towards that CENTRE. And for this purpose it extends an invitation to everyone, not just the members of the said community. There were times in history, when the Christian community spoke to the “world” with the intent of engulfing everything and – when needed – subject whole lives to its laws.

Those times are gone. Even though according to medieval customs village churches still are in the middle of the settlement, nowadays the Church and the Christian community raises its voice from the periphery. The compulsion to interfere in everything has disappeared. We rely on our internal freedom when conveying the message of the Gospel.

But what exactly is this message? Moreover, it must be carried by a language accessible not only to the “initiated”, but also to everybody who is part of the whole human community.

Firstly, we say that there is a reality higher than the one where we are able to rise. That there is a reality deeper than the one where we can sink. Reality is broader than our perception. At the same time, this Reality is much closer to human beings than they can be close to themselves.

This Reality relativises human acts and at the same time frees them from the prison of “it all depends on me”. It requires responsibility, because one will have to account for one’s life without being allowed to pronounce final judgements on others. The final judgement on the other does not belong to you!

We must spread the message of joy about the Reality that is not in man’s hands, is not in our hands, but is present in our lives and we have to do with it. Ultimately, we all have to do with Him in all our affairs.

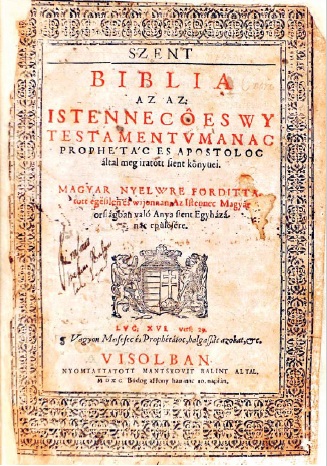

The Vizsoly Bible, the first complete Hungarian Bible translation by the Reformed minister Gáspár Károli and his colleagues, Vizsoly 1590, National Széchenyi Library, Budapest, 2412 pages

The Vizsoly Bible, the first complete Hungarian Bible translation by the Reformed minister Gáspár Károli and his colleagues, Vizsoly 1590, National Széchenyi Library, Budapest, 2412 pages

The great German-American theologian Paul Tillich termed this as “was uns unbedingt angeht”, “what necessarily relates to us”. The message is this: there is Someone who necessarily relates to humans, both individually and as a collectivity. Our job, our task is to speak about this “necessarily” even when everything in Hungary and the world at large is conditional. To tell that this Reality which necessarily relates to us is a/the loving Reality. This is the second part of the message.

We must ask the question: what does this message mean in public life? What does it mean in Protestant public life? It primarily means an image of man. Such a joint Christian – Catholic and Protestant – image of man that is different from those generally proposed by politics. Because behind every decision, every law, every government action there is an image of man.

What the administrators of healthcare think is in close connection with what they think about man. The way they conceive public education depends on what they think about the future generation. Their media policy, for example what they find acceptable or unacceptable in media is also determined by what they think about man.

The economy, the entertainment industry and every other segment of social reality has its own image of man. And we also have ours. We have our Biblical Christian image of man, which can be put beside or set against these other images. Provocation is allowed. Protest is allowed.

And whenever we discover common aspects in these images, we are glad to represent them. Why could politics not make the right decision from time to time? The possibility cannot be dismissed out of hand! Then people could also take its side. Support a policy, a public life, the work for the common good done by politicians with whom you share an image of man. Do they not work for the same man?

The Christian image of man considers and addresses people from the perspective of a loving Reality. This is the basis for the public role of the Protestant community. This is not a static image proposed by the Church(es); it rather shows the path or paths towards a loving Reality.

Portrait of István Bocskai, after Egidius Sadeler, engraving, Hungarian National Museum

Portrait of István Bocskai, after Egidius Sadeler, engraving, Hungarian National Museum

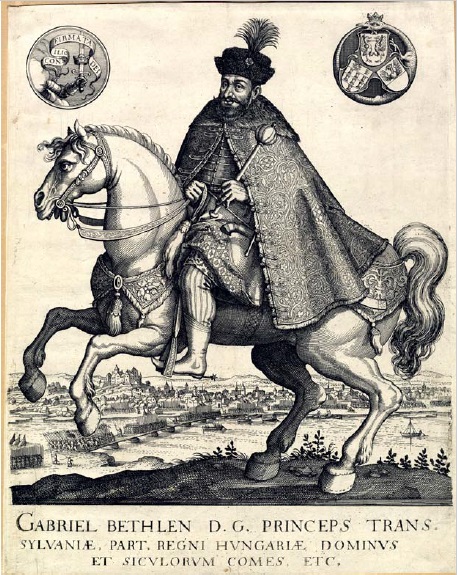

If we look at the 450-year history of Hungarian Protestantism, we can have an idea of the public role played by Protestants. From Bethlen to Bethlen we can enumerate everything we gave to the nation. The Transylvanian Prince Gábor Bethlen was born 437 years ago and Prime Minister István Bethlen, the saviour of post-Trianon Hungary died 71 years ago. The long line of Protestant leaders, public writers, artists and politicians spans from Bethlen to Bethlen.

We should not forget the ultimate sacrifice of Prime Minister István Tisza either. It could hardly be an accident that the perpetrators who meant harm to Hungary assassinated him on 31 October, Reformation Day. These great figures stand in a long line and everything they did for the country has a message for us. This is probably the best summary of how they saved this country. They saved it in the 17th, the 18th, the 19th and even the 20th century.

However, these are “only” consequences. They are merely means to an end. Because these heroes of the faith could only achieve greatness by living their faith, by relying on the message in question. They were aware that there is a loving Reality related to us and one can act in the name of and inspired by this Reality. Relying on this message the Protestant way is our fate and our duty.

Gábor Bethlen on horseback. Matthäus Meriansen., 1620, engraving, 33,9 x 27 cm, Hungarian National Museum

Gábor Bethlen on horseback. Matthäus Meriansen., 1620, engraving, 33,9 x 27 cm, Hungarian National Museum

How can one build one’s life on the message in a Protestant way? The Protestant differentia specifica is that nothing is about us as individuals, our acts are not self- serving, but are oriented towards this final Reality. The Protestant differentia specifica does not mean that we should do anything against the Catholics, nor does it mean that we have a special agenda. It simply means that we are not pointing to ourselves or to the Church, but to Him and through him to the other man. We must live according to this differentia specifica of ours not only to show others our individuality, but also because it tends to disappear from both Church rhetoric and everyday practice. We should add to the common fund our achievements, our heritage, our contribution to the country and this nation, both as individuals and as a community. One particularly interesting issue is how we as a community can realise in our life this pointing towards the other, towards God the saviour and the merciful. The Isenheim Altarpiece by Grünewald in Colmar, Alsace, depicts the Church pointing towards Jesus Christ. Saint John the Baptist stands below the crucifix and his larger-than-life index finger points towards the Crucified, the Lamb of God. The mission of our Church boils down to this.

Protestants can do their best for Hungary if they give an example of what it means to fight for the others, not oneself. We can show – because we know – that grace is not the goal but the starting point. Those who live in grace know that someone has already fought the fight for them, so they no longer need to fight for themselves but can fight for others. This is the differentia specifica of Protestants. The essence of Reformation is not the establishment of a new Church, but the will to inspire the entire Church.

The 20th century German Lutheran martyr theologian Dietrich Bonhoeffer warns us that when the Church asks the question: how can it get closer to the people, how can it catch up with our rushing modern world and what methods and practices it should employ in order to be understood by the young generation – it has already committed a mistake.

Because the first question should be: who is Jesus Christ, who is Jesus Christ for us, and this will automatically show us the way of how to introduce him to the ignorant. But we must first realise what he means to us. As Anselm of Canterbury wrote: “Let me receive That which you promised through your truth, that my joy may be full.” ... Credo ut intelligam.

Because we must present not ourselves, but Him to Hungary, to Europe, to all those who have not yet received this message. Behold the Lamb of God, who has taken upon himself the sins of the world. We do not point to ourselves, because sola gratia, only grace can change man and the community of men.

In the 21st century, the common question of the Reformed and the universal (Catholic) Church is this: will there be a common thought, a common space where we can all meditate upon what it means to live on grace? Because if we ourselves do not know it, how could others know?

We should avoid the traps described by an erstwhile German Lutheran and Calvinist anecdote. According to it, in the 17th century a Lutheran presbytery discussed whether Calvinists can find salvation. This being a ponderous topic, they debated it long and hard and finally – because they were all good brothers – came to the conclusion that Calvinists can indeed be saved.

But one of the presbyters, a stiff-necked Lutheran – there are those as well, not only stiff-necked Calvinists – said he will only sign the text that Calvinists can find salvation if he can add half a sentence. Be it so, the others said. So to the declaration that Calvinists can also be saved, came this small addendum of the Lutheran supervisor: but only really, truly through grace and faith.

Let us be of grace! Let us act in grace! This can best be translated into common parlance thus: let us make sure that we are due to the love of the ultimate, omnipotent Reality! We are in this world due to His love, therefore we can live by grace granted, and act through faith for the benefit of mankind and the Glory of God.