22 March 2018

About a Stained Glass Window Lost from View

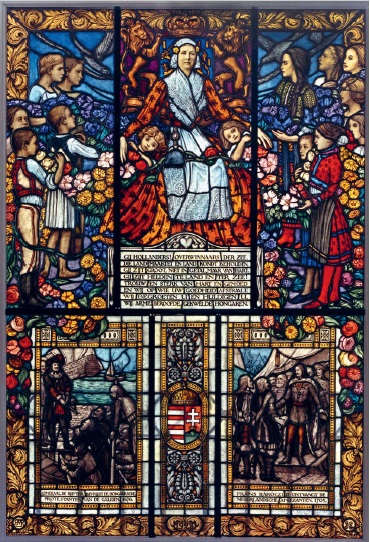

The Quincentennial of the Reformation supplies a particularly opportune moment to remember a stained glass window made by Hungarian masters known as Het Hongaarse Raam (“The Hungarian Window”), which made headlines in the press in 1923, when it was completed, but later somehow fell off the radar screen of researchers.1 Made by Miksa Róth based on a design by Sándor Nagy, the stained glass window was presented as a gift to Queen Wilhelmina of the Netherlands (1880–1962), who enjoyed immense popularity in Hungary, on the 25th anniversary of her reign.2 The composition illustrates three momentous junctures in Dutch–Hungarian relations, emphasising the power of Protestantism to forge communities and the altruistic service of religion.

Sándor Nagy (1869–1950), a leading proponent of Hungarian Art Nouveau, distinguished himself not only in painting but in graphic and applied art as well. Nagy started out as a disciple of Bertalan Székely, then went on to study in Rome and at the Académie Julian in Paris. Returning to Hungary, he settled down in the city of Veszprém, later joining the art community of Aladár Körösfői-Kriesch in Gödöllő (1901–1920). The senior masters of the community and its weaving workshop secured a string of commissions for murals, glass windows and mosaic walls to decorate a number of public buildings. From the turn of the century they were regular exhibitors at World Fairs. A superb draftsman and illuminator, Nagy often portrayed themes of the life reform movement and theosophy in his drawings. Róth’s stained glass windows decorating the Mirror Room of the Palace of Culture in Marosvásárhely (Tîrgu Mureș), based on Nagy’s carton illustrations to Transylvanian Hungarian folk ballads, are among the pinnacles of the Art Nouveau movement, in Hungary and elsewhere in Europe.

Miksa Róth (1865–1944) founded and spearheaded the best-known and most productive Hungarian atelier of stained glass, a medium that experienced a period of rejuvenation at the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries. Róth had mastered the craft in his father’s workshop before leaving for England, France and Germany to study medieval masterpieces in stained glass. Having set up his own shop in Budapest in 1885, he proceeded to design and manufacture lead frame stained glass windows and mosaics for several public buildings, city halls, banks, baths and private mansions. Among other high-profile projects, he was responsible for decorating Parliament, the Gresham Palace, the Saint László Church, and the perished Royal Castle Chapel. Miksa Róth was among the first artists in the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy to employ Tiffany glass, a new technique of glassmaking invented in America. Churches and public buildings incorporating his decorative works can be found throughout the territory of the former Austro-Hungarian Monarchy, as well as in many places around the world, from Norway to Mexico.

As for that precious gift for Wilhelmina, the lead frame stained glass window in its upper section depicts the Queen protectively embracing two children on either side. In the two side panels, children wearing Hungarian folk costume hold flower wreaths as they raise their gaze to the central figure. The tablet underneath the Queen is inscribed in Dutch with the following salutation:

“Hail the Dutch, conquerors of the sea, / creators and cultivators of the land, / who may be small in number but great in spirit. / Heroes of land and the seas, / loyal, strong and brave of heart: / We the recipients of your benevolence / salute and glorify You, / we poor Hungarians, a nation ravaged and tormented by the times.”3

In the lower left, the work depicts a scene with Admiral Michiel de Ruyter (1607– 1676), who in 1676 rescued Hungarian Protestant priests from fierce persecution during the Counter-Reformation, when those refusing to convert to the Roman Catholic creed were convicted to the galleys. The inscription underneath reads, “Admiral Ruyter rescues Hungarian Protestants from the galleys. 1676”. The scene on the right portrays “Prince Rákóczi II receiving envoys from the Netherlands. 1704”. Flanked by these two scenes in the lower section is Hungary’s national crest in a Baroque frame. The overall design of the window is conceived in the Historicist style, as befits the evocation of past events. The frame holding the parts together is composed of stylised tendrils with leaves and flowers.

The work is signed with the initials of Miksa Róth on the bottom left, and by Sándor Nagy and his wife, Laura Kriesch, on the right. The year of completion is given as 1923.

Stained glass window by Miska Róth based on the design of Sándor Nagy. 1923,

202 cm x 137 cm, Royal Collections of the Netherlands, The Hague.

© Royal Collections of the Netherlands, The Hague

In his book, Miksa Róth proudly reports on the reception of his stained glass work based on Nagy’s design: “Much praise was heaped on the stained glass work I made in collaboration with Sándor Nagy for the Royal Palace in the Hague. Back home, we felt profound gratitude for the Dutch, who had generously adopted hundreds of enfeebled Hungarian children for feeding and nursing [i.e. after the First World War – the editor]. To express our heartfelt thanks, on the initiative of the Dutch–Hungarian Society, Hungary offered Queen Wilhelmina the gift of a stained glass work of art to commemorate her 25th year on the throne. The window portrays the Queen wearing fries folk costume, with Hungarian children paying her a tribute of flowery garlands. This work in stained glass is on display on a wall personally designated by the Queen in the Beldensal [sic— correctly, Beeldenzaal — the author], one of the most wonderful rooms of the Royal Palace in the Hague.” Róth also quotes Queen Wilhelmina’s words of appreciation, as relayed to him by Oszkár Mendlik: “This window is extremely beautiful […] It pleases me a great deal.”4

In later times, many looked for this window in the Royal Palace in the Hague, but it was no longer to be found there. The mystery of its disappearance was explored by Melinda Kónya, a Hungarian librarian of the Dutch Royal Library, who sent us a Dutch publication describing the work of Sándor Nagy and Miksa Róth. As it turns out, the famous stained glass window had been moved to Noordeinde Palace (to the first floor of the western wing to the north, to be precise) where King Willem-Alexander keeps his studies off limits to visitors.5

Translation by Péter Balikó Lengyel

Notes:

1 Dimensions: 202 by 137 cm.

2 The Avenue in Budapest called “Városligeti fasor” today was originally named after Queen Wilhelmina, in 1921.

3 After the Hungarian translation from the Dutch, courtesy of Ákos Urbán.

4 Miksa Róth: Egy üvegfestőművész emlékei [Memories of a stained glass artist]. Budapest: 1943, pp. 52–54.

5 Emerentia van Heuven-van Nes: Nassau en Oranje in Gebrandschilderd Glas 1503–2005. Hilversum Verloren: 2015, pp. 164–166.